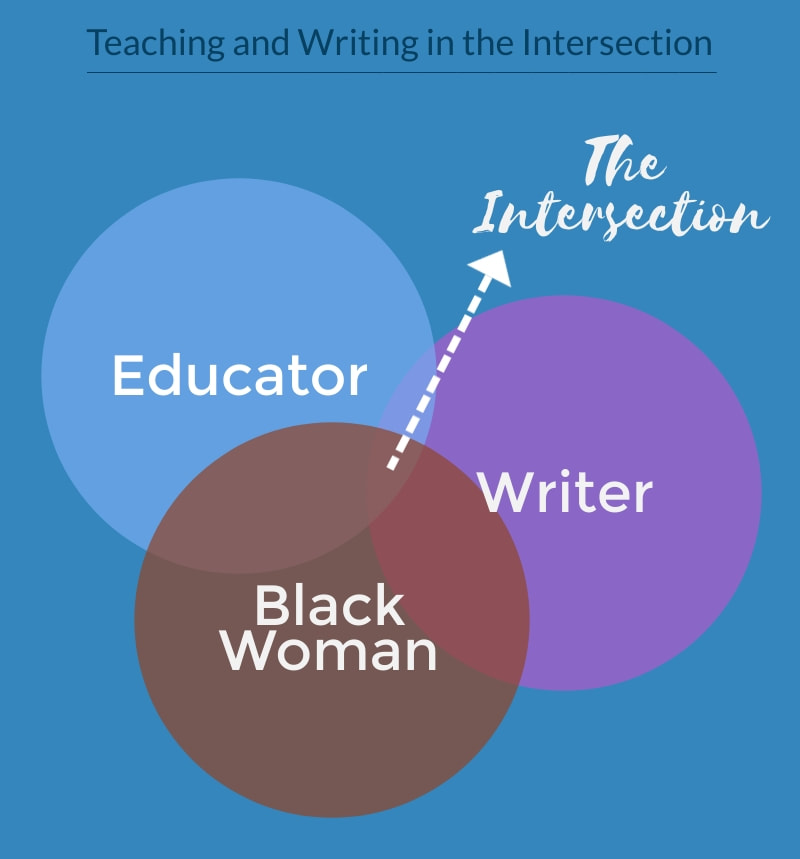

Who we are is shaped by many factors, those pushing from within and those from without. Colliding circles of who we are when we step into the world, who we want to be, and the compounding effects those identities.

Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw describes intersectionality in her paper exploring the oppression of Black women and the ways interlocking systems of power affect marginalized communities.

I am an educator.

I am a writer of children's literature.

I am a Black woman.

Each identity rings its notes and in the center I try to bend them towards harmony.

Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw describes intersectionality in her paper exploring the oppression of Black women and the ways interlocking systems of power affect marginalized communities.

I am an educator.

I am a writer of children's literature.

I am a Black woman.

Each identity rings its notes and in the center I try to bend them towards harmony.

Educator

I come from a family of strong women educators. My aunts and cousins are kindergarten teachers, third grade teachers, special education teachers, and high school counselors and social workers. Education has always been important.

Beginning in third grade, I was bused from my neighborhood in Boston to an affluent suburb on the South Shore to attend school. It was my first experience navigating a mostly white space as a Black girl. Amid opportunities and challenges, I thrived and made friends, but I also faced microaggressions; some I didn't recognize until later in life.

College was another mostly white space. I rose to meet challenges, but I also felt my otherness and something new, impostor syndrome. Was I good enough? Did I belong?

In education, I still find myself in predominantly white spaces, especially in independent schools. I count myself lucky to work in a school that is deliberate in its efforts to be inclusive and equitable, and prioritizes social justice. I have more colleagues of color than ever in my career and count many other colleagues as demonstrated allies. Yet, navigating the field as a person of color takes courage and vulnerability.

As a new English teacher many years ago, I was mentored by generous and supportive veteran educators, but I didn't feel empowered to question the literacy methods and curriculum I inherited. I followed along and became a good instructor, but...

Something I couldn't name felt off. I returned to school and developed the language for what I had been questioning.

Was I meeting the needs of my students who identified as other than white? How culturally responsive was my literacy instruction? Where in the curriculum were the voices of color and marginalized groups?

I began to assess and question my work critically.

What I recognized was that most of what we read and discussed in my fifth grade classroom centered the experiences of the white majority. We read books such as The Cay by Theodore Taylor and The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle by Avi–books that centered white characters who often learned about race and racism through the efforts and sacrifices of secondary characters of color.

How would I have felt as a Black girl in my own class reading these books? The answer saddens me.

Where on my shelves could students find mirror texts to accurately reflect their beautiful and varied identities? Stretched for money, I had built my classroom library using points earned from student orders from Scholastic Book Clubs. I ordered the books highlighted in its pages: Little House of the Prairie by Laura Ingalls Wilder, The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett, The Indian in the Cupboard by Lynne Reid Banks. Was I unconsciously presenting unchallenged stereotypes and poor representations through the reading choices I provided? Again, I was sad to realize the answer. Yes.

So, I changed.

What books are on my shelf now? I actively seek books by #OwnVoices authors and those who identify as Indigenous or as people of color. Books like:

These books reflect authentic voices of Indigenous and authors of color and positive representations in which students may find themselves, not only stories of oppression.

Teaching as a Black woman, I have learned that I have to be a voice that questions. Silence and accepting the status quo is the biggest sin I can commit.

I owe it to students to promote a literacy that is inclusive, authentic, and joyful. I owe it to them to question the canon. I owe it to them to take a critical stance towards every book we read together.

To do that, I must be equal parts learner and teacher.

Beginning in third grade, I was bused from my neighborhood in Boston to an affluent suburb on the South Shore to attend school. It was my first experience navigating a mostly white space as a Black girl. Amid opportunities and challenges, I thrived and made friends, but I also faced microaggressions; some I didn't recognize until later in life.

College was another mostly white space. I rose to meet challenges, but I also felt my otherness and something new, impostor syndrome. Was I good enough? Did I belong?

In education, I still find myself in predominantly white spaces, especially in independent schools. I count myself lucky to work in a school that is deliberate in its efforts to be inclusive and equitable, and prioritizes social justice. I have more colleagues of color than ever in my career and count many other colleagues as demonstrated allies. Yet, navigating the field as a person of color takes courage and vulnerability.

As a new English teacher many years ago, I was mentored by generous and supportive veteran educators, but I didn't feel empowered to question the literacy methods and curriculum I inherited. I followed along and became a good instructor, but...

Something I couldn't name felt off. I returned to school and developed the language for what I had been questioning.

Was I meeting the needs of my students who identified as other than white? How culturally responsive was my literacy instruction? Where in the curriculum were the voices of color and marginalized groups?

I began to assess and question my work critically.

What I recognized was that most of what we read and discussed in my fifth grade classroom centered the experiences of the white majority. We read books such as The Cay by Theodore Taylor and The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle by Avi–books that centered white characters who often learned about race and racism through the efforts and sacrifices of secondary characters of color.

How would I have felt as a Black girl in my own class reading these books? The answer saddens me.

Where on my shelves could students find mirror texts to accurately reflect their beautiful and varied identities? Stretched for money, I had built my classroom library using points earned from student orders from Scholastic Book Clubs. I ordered the books highlighted in its pages: Little House of the Prairie by Laura Ingalls Wilder, The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett, The Indian in the Cupboard by Lynne Reid Banks. Was I unconsciously presenting unchallenged stereotypes and poor representations through the reading choices I provided? Again, I was sad to realize the answer. Yes.

So, I changed.

What books are on my shelf now? I actively seek books by #OwnVoices authors and those who identify as Indigenous or as people of color. Books like:

- The Bridge Home by Padma Venkatraman

- Blended by Sharon Draper

- The Serpent's Secret by Sayantani DasGupta

- Watch Us Rise by Renée Watson and Ellen Hagan

- Amal Unbound by Aisha Saeed

- The Vanderbeekers of 141st Street by Karina Yan Glaser

- Skeleton Man by Joseph Bruhac

- Esperanza Rising by Pam Muñoz Ryan

- The New Kid by Jerry Craft

- The Jumbies by Tracey Baptiste

- A Good Kind of Trouble by Lisa Moore Ramée

- Amina's Voice by Hena Kahn

- Sal and Gabi Break the Universe by Carlos Hernandez

These books reflect authentic voices of Indigenous and authors of color and positive representations in which students may find themselves, not only stories of oppression.

Teaching as a Black woman, I have learned that I have to be a voice that questions. Silence and accepting the status quo is the biggest sin I can commit.

I owe it to students to promote a literacy that is inclusive, authentic, and joyful. I owe it to them to question the canon. I owe it to them to take a critical stance towards every book we read together.

To do that, I must be equal parts learner and teacher.

Writer

Publishing is another field that is overwhelmingly white and female. When I audited my classroom library and reading lists, I shared with a colleague my disappointment about the the lack of voices of color in our curriculum. Her response? "You should write a book." I blinked and thought, Yes, I should!

Fantasy was my beginning, a genre I loved as a young reader. I thought back to the books I read as a child.

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L'Engle, The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis, The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster, Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of Nimh by Robert C. O'Brien, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl.

What do you notice about this list of books?

Yup. Overwhelmingly white. Growing up in the 1970s and 80s, if I found a book by a Black author in my elementary and middle school libraries, it was usually historical or realistic fiction. Often it didn't reflect the middle class family and environment in which I lived.

I wanted to write something different. A book that "middle-school-me" would have curled under the covers with a flashlight to read. A book where a girl like me could see herself on a magical adventure.

Fantasy was my beginning, a genre I loved as a young reader. I thought back to the books I read as a child.

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L'Engle, The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis, The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster, Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of Nimh by Robert C. O'Brien, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl.

What do you notice about this list of books?

Yup. Overwhelmingly white. Growing up in the 1970s and 80s, if I found a book by a Black author in my elementary and middle school libraries, it was usually historical or realistic fiction. Often it didn't reflect the middle class family and environment in which I lived.

I wanted to write something different. A book that "middle-school-me" would have curled under the covers with a flashlight to read. A book where a girl like me could see herself on a magical adventure.

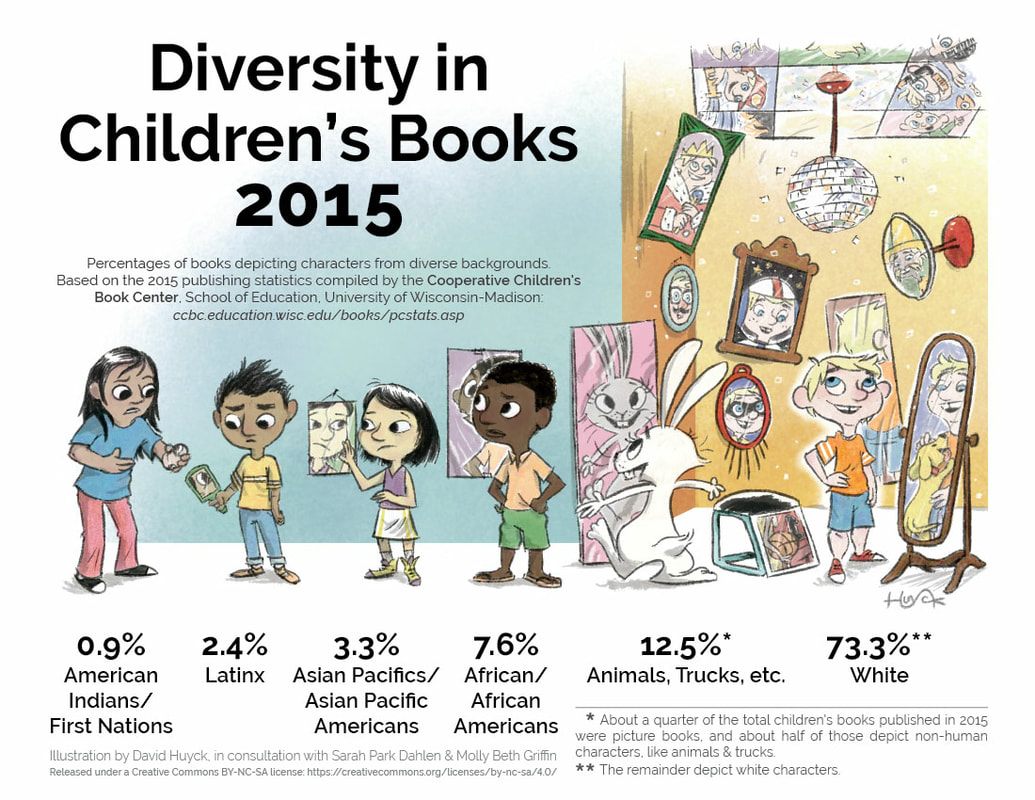

Huyck, David, Sarah Park Dahlen, Molly Beth Griffin. (2016 September 14). Diversity in Children’s Books 2015 infographic. sarahpark.com blog. Retrieved from https://readingspark.wordpress.com/2016/09/14/picture-this-reflecting-diversity-in-childrens-book-publishing/

Released for non-commercial use under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

Released for non-commercial use under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

Here are some sobering facts. The number of books that contain multicultural content over the past 24 years, remains a low 13%. In addition, Black, Latinx, and Native authors combined wrote only 7% of all books for children published in 2017. A children's book is more likely to depict a main character that is an animal or inanimate object than a child of color.

So, I started writing. Being a consumer of children's books, I somehow held the wild misbelief that this writing would flow easily. *Queue laughter*

Alas, teaching children's literature is like riding in a car driven by an expert driver. Writing it is not the same.

Keep your hands on the wheel. Learn to steer. Figure out the gears. What do these buttons on the dash do?

I joined the Society of Children's Book Authors and Illustrators (SCBWI), the professional organization for those in kidlit, found a critique group, and started learning my craft. I attended workshops and conferences. I drafted. Revised. Revised again. Did I mention that I revised?

Thankfully, the needle is moving toward greater inclusivity and representation for authors of color in the children's publishing industry. Books like Angie Thomas's The Hate U Give and Samira Ahmed's Internment have shown that kids and communities of color do read and want more books that speak to them. Unlike "middle-school-me," my students can name many authors of color who write amazing stories with imagination and truth.

Still, breaking through in publishing is hard. Finding agents and editors who connect with stories and voices that may be outside of their experience is a challenge. Connecting with mentors and fellow writers of color is important to sustaining a career.

Many of us have found affinity groups and support within the greater kidlit community through Twitter, Facebook groups, organizations like #WeNeedDiverseBooks and the I, Too Arts Collective, and events like the Kweli Color of Children's Literature Conference. Publishing has also responded with mentorship opportunities like The Highlights Foundation Diversity Fellowship and publishing imprints like Kokila and Rick Riordan Presents, both of which center stories told by authors from traditionally marginalized groups.

I've come a long way in six years. I successfully queried my first middle grade fantasy manuscript and am agented by the fabulous Lindsay Davis Auld at Writers House. But publishing is a long game. It takes years from query, to submission, to book contract, and finally publication. In the meanwhile, you need to write the next thing.

I've learned to stop talking about my writing sheepishly, like it is a hobby or distraction that I do on the side. It's important. Not only for me as a fuel for creativity, but as a real-world model of writing for my students.

Why do I write?

I write for that kid. The one just like me, waiting to see herself in an adventure. The brown-skinned hero of a fantasy, off saving the world.

So, I started writing. Being a consumer of children's books, I somehow held the wild misbelief that this writing would flow easily. *Queue laughter*

Alas, teaching children's literature is like riding in a car driven by an expert driver. Writing it is not the same.

Keep your hands on the wheel. Learn to steer. Figure out the gears. What do these buttons on the dash do?

I joined the Society of Children's Book Authors and Illustrators (SCBWI), the professional organization for those in kidlit, found a critique group, and started learning my craft. I attended workshops and conferences. I drafted. Revised. Revised again. Did I mention that I revised?

Thankfully, the needle is moving toward greater inclusivity and representation for authors of color in the children's publishing industry. Books like Angie Thomas's The Hate U Give and Samira Ahmed's Internment have shown that kids and communities of color do read and want more books that speak to them. Unlike "middle-school-me," my students can name many authors of color who write amazing stories with imagination and truth.

Still, breaking through in publishing is hard. Finding agents and editors who connect with stories and voices that may be outside of their experience is a challenge. Connecting with mentors and fellow writers of color is important to sustaining a career.

Many of us have found affinity groups and support within the greater kidlit community through Twitter, Facebook groups, organizations like #WeNeedDiverseBooks and the I, Too Arts Collective, and events like the Kweli Color of Children's Literature Conference. Publishing has also responded with mentorship opportunities like The Highlights Foundation Diversity Fellowship and publishing imprints like Kokila and Rick Riordan Presents, both of which center stories told by authors from traditionally marginalized groups.

I've come a long way in six years. I successfully queried my first middle grade fantasy manuscript and am agented by the fabulous Lindsay Davis Auld at Writers House. But publishing is a long game. It takes years from query, to submission, to book contract, and finally publication. In the meanwhile, you need to write the next thing.

I've learned to stop talking about my writing sheepishly, like it is a hobby or distraction that I do on the side. It's important. Not only for me as a fuel for creativity, but as a real-world model of writing for my students.

Why do I write?

I write for that kid. The one just like me, waiting to see herself in an adventure. The brown-skinned hero of a fantasy, off saving the world.

Black Woman

I am an educator.

I am a writer of children's literature.

I am a Black woman.

I stand in the intersection using my words to call for justice and change through literacy.

Whether in the pages of a book I read to my students or one that I write for children, I am finding my voice.

I am a writer of children's literature.

I am a Black woman.

I stand in the intersection using my words to call for justice and change through literacy.

Whether in the pages of a book I read to my students or one that I write for children, I am finding my voice.

#31DaysIBPOC

This blog post is part of the #31DaysIBPOC Blog Challenge, a month-long movement to feature the voices of Indigenous and teachers of color as writers and scholars. Please CLICK HERE to read yesterday’s blog post by Antero Garcia (and be sure to check out the link at the end of each post to catch up on the rest of the blog circle).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed