It happens more often now. That awkward pause. A tightness in my stomach. The choice. Do I let the moment pass or do I say something?

Silence is a choice.

I’m not the same person I was fifteen, ten, or even five years ago. A younger-me was sometimes unaware of the subtle or not-so-subtle inequities and injustices around me. And other times, I simply looked the other way.

We live in a country that does not treat all of its people compassionately, equitably, or justly. I’ve always known this. Growing up a Black girl in Boston, how could I not? But I’m also a pleaser—a don’t-rock-the-boater. As a Black girl, and now a Black woman navigating mostly white spaces, I’ve learned to find my place and fit in. Over the years as a teacher and now as a writer, I’ve accepted that and enjoy the relationships I’ve made in schools, in writing organizations, and in various online spaces.

And yet those uncomfortable moments don’t go away. They’re frequent. My white friends and colleagues may be surprised to know how often POC feel those small and not-so-small stings to the spirit. The proposal of another all-white booklist or an all-white conference panel. Problematic classroom favorites that are recommended again and again. Microaggressions that tear down self-esteem (and the need to explain those microaggressions to others). As a teacher, I value the teachable moments when I get to gently open my students’ awareness to their privileges and the inequities of the systems in which we all live and breathe. Yet with adults, sometimes it’s harder to pull forth the energy to speak.

Sometimes, the choice is whether the issue is worth spending the emotional capital you have saved. Do you have it to spend? How many times have you raised a similar issue before? Is it worth the risk of sliding into the stereotype of the “angry Black woman” or appearing difficult or dissatisfied? All emotional labor that non-WOC often do not bear.

Yet still, I don’t look away anymore; I can’t. But I look around.

I notice who is quiet and wonder if anyone else will speak. Often, it’s other women of color. Why is that? It’s not fun. It’s not easy. There’s often greater pushback for us.

Sometimes, there is defensiveness when racist or inequitable practices are brought up or remedied, as in the renaming of the ALA’s Children’s Legacy Award (previously the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal) or the NEA’s decision to rebrand the Read Across America program and leave behind Dr. Seuss.

Other times, there is silence from those that perhaps feel themselves allies. In her article “Nothing to add: A Challenge to White Silence in Racial Discussions,” Robin DiAngelo explores the causes for “white silence” when race is on the table. The reasons vary from feeling “I have nothing to add” to “I don’t want to be misunderstood” and “It’s not my personality to share in groups,” but despite the personal validity people may feel in their reasons, they all function to support white privilege and power in situations involving race. There are times when non-POC friends and colleagues should rightly sit back and listen, but those situations usually involve intra-community issues. When POC share their experiences of oppression or injustice, silence only invalidates the message being delivered.

Personally, I’ve left three different Facebook educator groups this year that I had joined for professional development. Unfortunately, instead of growth and enrichment, I found the opposite was true in each instance. My interactions in these spaces left me feeling drained. If someone posted a question or comment that had problematic content related to diversity, equity, or inclusion, I gently tried to push back or share my knowledge in order to help and support my fellow teachers. Sometimes, it was received well, but more often than not, there was a “digging in” around the problematic opinions and practices.

And from others, there was often silence.

In a recent interview at the WOW Women of the World Festival at the Apollo Theater, poet Nikki Giovanni said, “One of the things I think is missing right now, is we seem to be spending time telling white people what they're doing wrong, instead of telling Black people what we're doing right." She praised the wit and bravery of Black women like Representative Maxine Waters as she speaks against Donald Trump's oppressive policies, but Giovanni recognized the toll it takes, and has taken on Black women in the past, to do this work. Her advice was “lean on the everlasting arms” and connect to our past for strength.

That made me think. Who came before us and chose to speak? Ida. Claudette. Georgia. Who came before me? Rosa Simmons Giddis, my grandmother.

Born in 1920 in Union Spring, Alabama, my grandmother "Momma" married young to my grandfather Earnest “Chick” Simmons. By the time she was 17, she had two children, and when she was just 33 years old and her husband was killed in a coal-mining explosion, she was left to raise ten children on her own.

Silence is a choice.

I’m not the same person I was fifteen, ten, or even five years ago. A younger-me was sometimes unaware of the subtle or not-so-subtle inequities and injustices around me. And other times, I simply looked the other way.

We live in a country that does not treat all of its people compassionately, equitably, or justly. I’ve always known this. Growing up a Black girl in Boston, how could I not? But I’m also a pleaser—a don’t-rock-the-boater. As a Black girl, and now a Black woman navigating mostly white spaces, I’ve learned to find my place and fit in. Over the years as a teacher and now as a writer, I’ve accepted that and enjoy the relationships I’ve made in schools, in writing organizations, and in various online spaces.

And yet those uncomfortable moments don’t go away. They’re frequent. My white friends and colleagues may be surprised to know how often POC feel those small and not-so-small stings to the spirit. The proposal of another all-white booklist or an all-white conference panel. Problematic classroom favorites that are recommended again and again. Microaggressions that tear down self-esteem (and the need to explain those microaggressions to others). As a teacher, I value the teachable moments when I get to gently open my students’ awareness to their privileges and the inequities of the systems in which we all live and breathe. Yet with adults, sometimes it’s harder to pull forth the energy to speak.

Sometimes, the choice is whether the issue is worth spending the emotional capital you have saved. Do you have it to spend? How many times have you raised a similar issue before? Is it worth the risk of sliding into the stereotype of the “angry Black woman” or appearing difficult or dissatisfied? All emotional labor that non-WOC often do not bear.

Yet still, I don’t look away anymore; I can’t. But I look around.

I notice who is quiet and wonder if anyone else will speak. Often, it’s other women of color. Why is that? It’s not fun. It’s not easy. There’s often greater pushback for us.

Sometimes, there is defensiveness when racist or inequitable practices are brought up or remedied, as in the renaming of the ALA’s Children’s Legacy Award (previously the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal) or the NEA’s decision to rebrand the Read Across America program and leave behind Dr. Seuss.

Other times, there is silence from those that perhaps feel themselves allies. In her article “Nothing to add: A Challenge to White Silence in Racial Discussions,” Robin DiAngelo explores the causes for “white silence” when race is on the table. The reasons vary from feeling “I have nothing to add” to “I don’t want to be misunderstood” and “It’s not my personality to share in groups,” but despite the personal validity people may feel in their reasons, they all function to support white privilege and power in situations involving race. There are times when non-POC friends and colleagues should rightly sit back and listen, but those situations usually involve intra-community issues. When POC share their experiences of oppression or injustice, silence only invalidates the message being delivered.

Personally, I’ve left three different Facebook educator groups this year that I had joined for professional development. Unfortunately, instead of growth and enrichment, I found the opposite was true in each instance. My interactions in these spaces left me feeling drained. If someone posted a question or comment that had problematic content related to diversity, equity, or inclusion, I gently tried to push back or share my knowledge in order to help and support my fellow teachers. Sometimes, it was received well, but more often than not, there was a “digging in” around the problematic opinions and practices.

And from others, there was often silence.

In a recent interview at the WOW Women of the World Festival at the Apollo Theater, poet Nikki Giovanni said, “One of the things I think is missing right now, is we seem to be spending time telling white people what they're doing wrong, instead of telling Black people what we're doing right." She praised the wit and bravery of Black women like Representative Maxine Waters as she speaks against Donald Trump's oppressive policies, but Giovanni recognized the toll it takes, and has taken on Black women in the past, to do this work. Her advice was “lean on the everlasting arms” and connect to our past for strength.

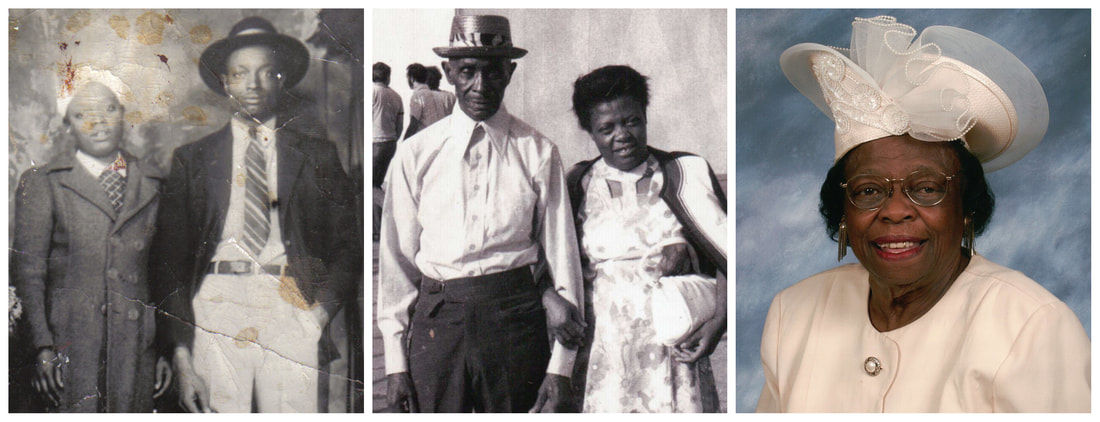

That made me think. Who came before us and chose to speak? Ida. Claudette. Georgia. Who came before me? Rosa Simmons Giddis, my grandmother.

Born in 1920 in Union Spring, Alabama, my grandmother "Momma" married young to my grandfather Earnest “Chick” Simmons. By the time she was 17, she had two children, and when she was just 33 years old and her husband was killed in a coal-mining explosion, she was left to raise ten children on her own.

Left: Momma on her wedding day to Earnest Simmons; Middle: Momma and her second husband Mr. Giddis; Right: Momma and one of the fabulous hats she often wore to church

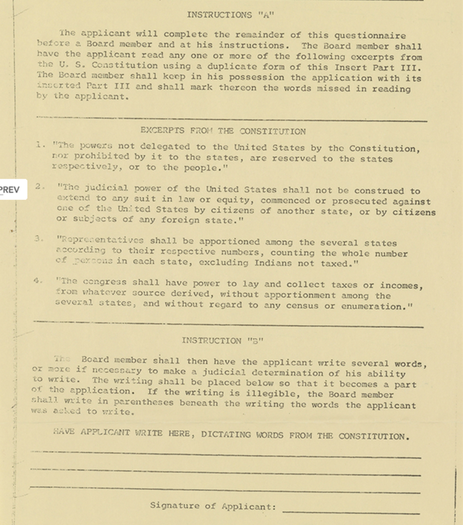

Despite the hardships of supporting a family of eleven as a widow, she saw the injustices around her and took action. She was an active supporter of civil rights and attended weekly meetings at the local church. Momma knew that mobilizing Black people to vote was a way forward. She encouraged the people in her little coal-mining town of Docena to register to vote. Of course, they were scared. Threats of violence were real. Other barriers to voting existed too, like the voting tests. African Americans had to pass a literacy test that included passages from the Constitution in order to prove they were qualified to vote. Momma asked her children to quiz her on her facts so she could pass the test. She later participated in the marches from Selma to Montgomery and in Washington, DC.

1964 Alabama Voter Literacy Test - Library of Congress

But she didn’t do these things alone, and nor should any of us. Allies are needed, but those allies must recognize that the work is for our collective benefit. There can't be "us" and "them." Only we. When addressing issues that impact the lives of children, there is no place for saviors; no place for silence.

Black women and other women of color know that speaking up will always have risks. The outcome is uncertain. When fatigue sets it, you question if your efforts will make a difference. But when you make a commitment to be reflective and antiracist, that choice leads towards action.

When I think of Nikki Giovanni’s words, I think of Momma. The mantle of her example lies before me and I wonder at its weight and beauty.

So, I commit to celebrate the achievement and excellence in our communities of color and to, as Nikki Giovanni so eloquently said, "tell Black people what we're doing right."

I commit to more self-care to keep my creative light alive and bright.

And, I’ll continue to use my voice in support of equitable and inclusive systems and practices in education and in the kidlit community. For Momma, for my children and the children I teach, and for myself, I'll keep speaking up.

But it’s exhausting.

This blog post is part of the #31DaysIBPOC Blog Challenge, a month-long movement to feature the voices of Indigenous, Black, and people of color as educators, writers and scholars. Please CLICK HERE to read yesterday’s blog post by Dr. Sarah Park Dahlen and CLICK HERE to read tomorrow's post by Michelle H. Martin and Edith Campbell.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed